(I originally wrote this blog months ago, but held off on publishing it. My hesitation came from a concern that it might be interpreted in ways beyond its intended purpose for the church. I hope that it will now be received as I felt led to share it—not as a political statement, but as a theological one.)

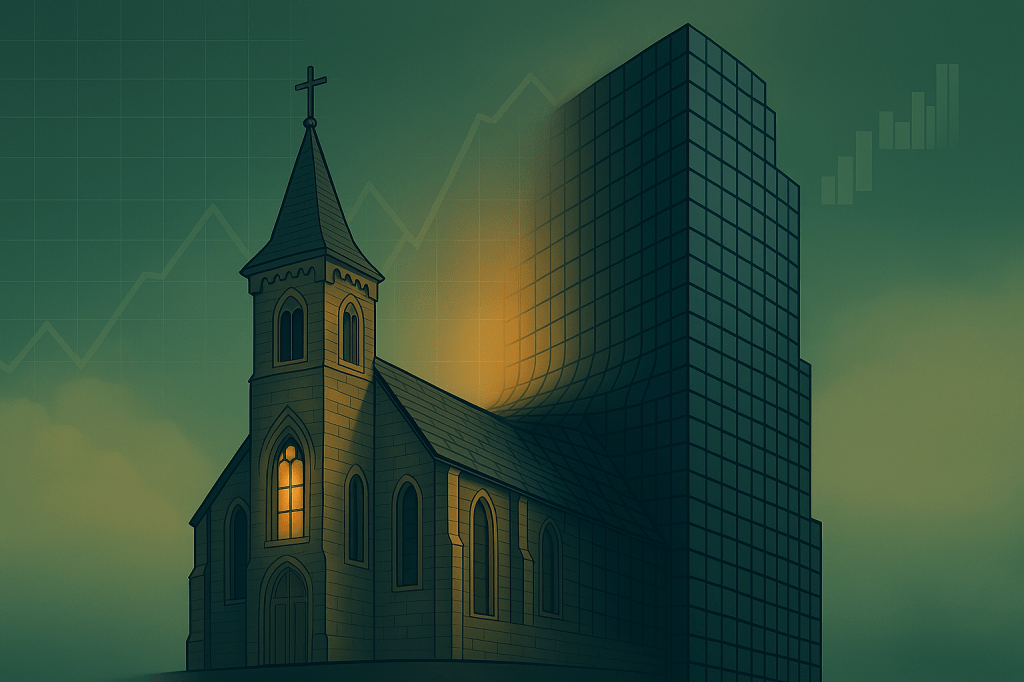

Dear Lord, Save Us from the god of “Pragmatism”!

I find myself deeply troubled—not necessarily by the same things that might concern you, but compelled to address some significant issues that I see gaining traction within the church.

Here’s the irony: I’ve always been a relentless pragmatist. I’ve never minded wearing the black hat, making the hard call, and doing what needs to be done. But lately, I’ve been forced to take a hard look in the mirror.

Let’s look at how Merriam-Webster defines pragmatism:

1: a practical approach to problems and affairs

2: an American movement in philosophy founded by C. S. Peirce and William James and marked by the doctrines that the meaning of conceptions is to be sought in their practical bearings, that the function of thought is to guide action, and that truth is preeminently to be tested by the practical consequences of belief

That second one on the origins of pragmatism gets me. If truth is only measured by the practical consequences of belief in the physical world, then faith—real faith—stands on fragile ground. In this light, pragmatism doesn’t serve the Church; it stands in potential tension with it. Leaving the Cross of Christ is impossible to sell through a purely pragmatic worldview.

So we have to ask: Is success solely about short-term gains and visible wins? Or should it also be measured by long-term consequences and spiritual formation?

What happens when we undercut the foundations of the church for the sake of a fast win?

Let me be clear—this isn’t about politics, denominationalism, or even the pursuit of achieving great things for the sake of the gospel. I’m all about what works, but I’m starting to ask a deeper set of questions. Is this working, or are we just spinning our wheels and putting on a show? Are we truly advancing the Kingdom of God, or are we simply pursuing our agendas under the guise of “pragmatism”? It’s about the price we pay for the power we choose to wield to impose our will.

This question exists at the nexus between the words “power” and “authority,” and it is the presence or absence of authority that separates good leadership from godly leadership and ruthless pragmatism. After all, true spiritual authority comes from God alone and is rooted in humility, love, and service. Yet, in our pursuit of success and influence, we often sacrifice these values at the altar of pragmatism.

Let me be clear up front: this isn’t about Trump. It’s not about Biden. It’s not about your favorite or least favorite politician. It is about the continued decline of our most honored offices and the collapse of our collective moral compass.

To name it simply, I’m concerned about the slow, almost invisible shift that’s happened to the office of the American presidency over the past several decades—a shift that mirrors something even more troubling happening within the Church.

Take, for instance, executive orders were once tools for enforcing the laws of Congress. By definition, executive orders cannot “create” law, appropriate funds, or overrule Congress. (FDR & Woodrow Wilson, signed enough to make you wonder if they had stock in BIC) Today, however, they increasingly serve as tools to create entirely new policies, carrying the same authority as law. This is particularly evident during periods of congressional gridlock. Rather than simply providing clarity, these orders often aim to swiftly navigate uncharted territory. And while that may seem like an effective workaround, it reveals something deeper: we’re increasingly willing to sacrifice process and principle for speed and results.

We’ve fallen in love with the god of pragmatism.

If it works, do it. If it gets results, who cares how? If it moves the needle, then the ends justify the means. While such a mindset is troubling in the realm of politics, it becomes profoundly more dangerous when it takes hold within the Church.

Here’s what I’ve observed: decisions that were once rooted in prayer, communal wisdom, the church’s historic traditions, and thoughtful discernment are increasingly driven by strategy decks, game theory, and growth metrics. Traditions that formed the backbone of Christian life are tossed aside for being “inefficient.” And structures that once shaped saints are dismantled in the name of “relevance.” If it seems like it might be effective, then let’s give it a go.

We have confused what is useful with what is faithful. We might be introducing people at a quicker rate, but what are we introducing them to? Have we become so obsessed with success and growth that we have lost sight of our true purpose and calling as the Church?

The message lies within the media itself.

Here’s the truth we don’t like to admit: just because something is cumbersome doesn’t make it wrong. Sometimes, discernment is made in the struggle. Sometimes the slowness, the messiness, the hard conversations, and collective wrestling are exactly what keep us grounded in Christ rather than chasing the next big thing.

Last week, I had the opportunity to hold my church people hostage as I talked about TRADITION! and the role of the church in the ages past. I got to bore them with history about councils and creeds. Specifically, I got to talk about the role of councils in discerning our understanding of the Trinity. Friends, these discernments were not made in a single moment but over centuries, spanning from the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D. to the Third Council of Constantinople in 681 A.D. This is not to suggest that the mystery of the Trinity was unknown until these dates, but rather that a lengthy and deliberate process was required to refine and formalize this foundational belief. During this period, the Church convened numerous councils to establish a high Christology of Jesus and to confront heresies such as Arianism, Pneumatomachianism, and Monothelitism. This journey reflects the Church’s commitment to clarifying and safeguarding its core doctrines. (If you don’t know these as sight words… join the club, I had to sound them out and look them up too)

The point is this: the Church has always been a slow, messy, and imperfect process. But in that very imperfection lies its beauty and faithfulness to God’s calling. If we continue down the path of pragmatism and forsake this process, we may find ourselves losing the very soul of the Church in our misguided pursuit of success.

What if Jesus streamlined the disciple-making process for the original 12?

Imagine if Jesus, instead of leading a three-year immersive rabbinical journey with his disciples, opted to condense it into six-weekend power summits—guided by Washington lobbyists, church consultants, and leadership experts. The idea is absurd because sometimes it is not solely about the outcome; it is about the incarnational means of delivery.

I think we see ruthless pragmatism in the Scripture in the ministry of Jesus. Especially in passages like Matthew 7:21-23

“Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven. Many will say to me on that day, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name and in your name drive out demons and in your name perform many miracles?’ Then I will tell them plainly, ‘I never knew you. Away from me, you evildoers!’

Some may argue that this interpretation stretches the exegetical boundaries a bit too far, but consider this: false disciples adopted the name of Jesus for a reason—because it worked. It got results, made an impact, and achieved their goals. They may have even convinced themselves that they were truly following Jesus, when they were just using his name as an effective means to an end…

And yet, we often want/demand immediate answers and solutions in the Church today. Truthfully, we may not always care about the cost as long as we have more people to show for it. There is a profound difference between someone who has spent six eventful weekends with Jesus and someone who has shared three years of life with Him—eating, laughing, praying, weeping, and witnessing their friend and Savior endure the cross.

For those of us in the Wesleyan tradition, it’s true that we’ve often acted in the name of “practicality,” aiming to align ourselves with Wesley’s example. Let me be clear—Wesley was indeed a practical man. However, the unrestrained pragmatism we witness in the church today seems like something that would be entirely unfamiliar to him. (If you want a deeper understanding of this, read Langford’s Practical Divinity: Theology in the Wesleyan Tradition) Wesley was practical, yet he refused to sacrifice the essence of the church for the fleeting allure of a silver-bullet or current trending solutions.

I don’t claim to have all the answers. I am simply a ruthless pragmatist questioning whether this is truly the right path for the Church. These are not easy questions, but they are essential ones we must confront together. We cannot continue chasing success at any cost, compromising our values and principles along the way. Instead, we must remember that true faithfulness to God’s calling is rarely easy or efficient. It is this steadfast dedication and discipleship that will lead us to true success, the kind that Jesus himself will acknowledge.

When pragmatism becomes the default setting of the Church, we stop asking what is holy and only ask what is helpful. We become obsessed with movement, forgetting that the Spirit often shows up in the waiting. We trade the formation of disciples for the management of consumers.

God free us from the false god of our pragmatism!

Not everything that gets results brings life.

And not every god that gets results is worth worshiping.

This post is the beginning of a larger conversation I’m calling Freeing the Church—a call to question what is motivating us in the modern church. I think we get a lot right, and by all means, I want to see people claim the name of Jesus; we just need to be sure we are introducing them to him and not to ourselves.

Leave a comment